Where are the ultra high agency boddhisatvas?

A couple of years ago I went down the rabbit hole of educating myself on our civilization’s meta-crisis. At the end of my studies, I found myself asking one fiendishly simple question:

Should I do something, or should I do nothing?

History is littered with the wreckages of well-intentioned people who tried to fix things and ended up making them worse. Sometimes much worse.

These are stark reminders that doing something doesn’t always help. Sometimes doing nothing is wiser. The Boddhisatva are arguably among the greatest forces for good in our world. Many will honor their vow (to free all beings from suffering) by living in a monastery, and simply engaging in loving-kindness meditation all day long.

Still, countless souls carry the energy, talent and influence to move the world, and have an undeniable drive to do something in service of love.

Where are the ultra high agency boddhisatvas?

The Materialist View on Doing Something

To be fair, decades of effort have gone into building systems designed to do good in the world.

I saw this firsthand earlier this year when I stepped into a role leading a startup. Our mission is to build a market that channels large amounts of capital into investments with verifiable environmental and social impact, while avoiding perverse outcomes.

The core thesis is simple: we have a funding gap of something like $3-10 trillion a year to start reversing the damage we’ve done to our planet and society. Those shortfalls show up as poverty, disease, homelessness, vanishing species, polluted waterways, deforestation, the quiet infiltration of microplastics into our environment and our bodies – the many faces of suffering that our civilization’s superorganism keeps feeding.

$3-10 trillion might sound like a big number, but in the grand scheme of things it’s really not. Even the high end is just a fraction of the world’s $270 trillion in managed assets.

The means to change our world already exist. What we are playing with are the roadblocks that stop that capital towards change for the better, and the incentives that direct it.

But is it really that simple? Of course not. Recent history is full of attempts to hijack profit-seeking and other engrained incentive structures to serve for good. Think of examples like:

Make pollution expensive so cutting it becomes profitable.1

Turn ‘trash into cash’ through bottle deposits schemes.

Paying only for real impact outcomes.2

Linking the cost of capital to impact.3

The formula is usually the same:

pick a behavior —> attach a $$$ price to it —> measure outcomes —> reward or penalize automatically

It sounds good in theory and yet here we are, still facing a growing metacrisis. That’s partly because it’s an oversimplified approach to what is, in reality, a much messier, complex and deeply systemic set of problems.

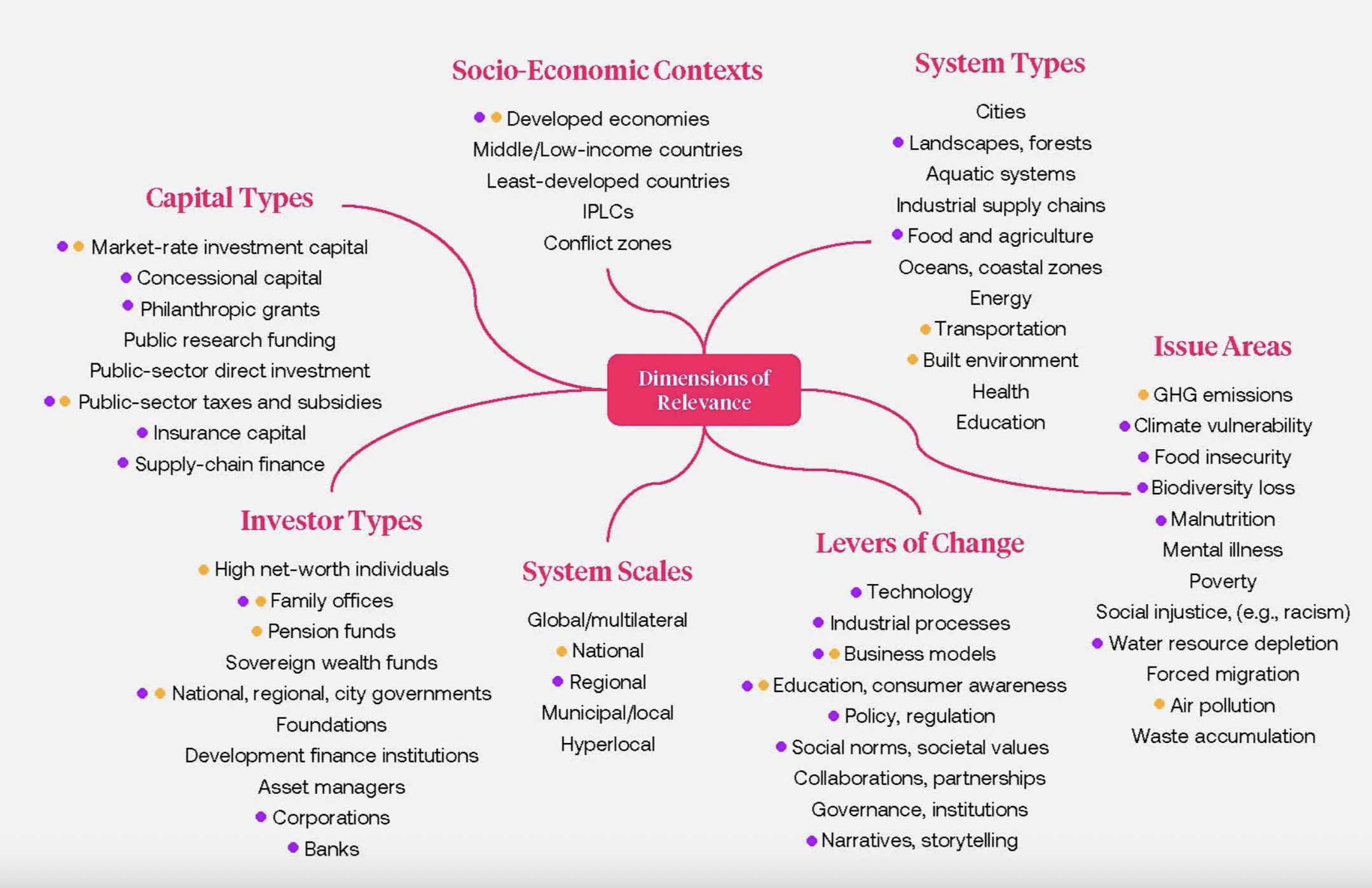

Thankfully, a growing number of practitioners are moving beyond this linear mindset, using frameworks like theory of change and systemic investing to capture the deeper complexity of transformation.

The common explanation for why hijacking profit-seeking hasn’t worked very well is pretty straightforward: societal and environmental problems are complex. They’re full of externalities and second-order effects we can’t easily predict. Those in the impact investing industry like to call them 'perverse outcomes’.

It’s not enough to simply treat symptoms. If we want to do something within the confines of the world we find ourselves in, we need deeper surgery. We need transformation at a more fundamental level.

This much seems obvious. And while I’m keenly interested in finding practical ways to enact systems transformation for good, I can’t help knowing that even these conversations are still missing something. A deeper rationale that sits beneath it all.

The Mystics View on Doing Something

I recently read a quote by Arne Naess, who’s life work centers on the human relationship with nature and who coined the term “deep ecology”.

Arne writes along the lines of:

altruism is a treacherous basis for conservation; we change only by realizing that nature is part of who we are, an act of genuine self-love toward an expanded sense of self; we change through identification.

Arne talks of a deep, embodied recognition that we are not separate from the living world but are in fact expressions of it. This requires a full shift in perception. It also requires us to engage a different type of knowing.

From a materialist standpoint many will say “well of course I’m separate”. The quiet assumption that we’re all isolated individuals sits at the very core of how capital markets, science in general, and even very frontier systems thinking tend to operate.

This assumption, like so many others, is based on one way of knowing called propositional knowing. A knowing that is based on facts and concepts, underpinned by a particular world view. But if our knowing stops there, we’re just skimming the surface of what it truly means to know.

There are at least 3 deeper forms of knowing:

- Procedural knowing – the knowing that comes through doing, which leads to embodiment.

- Perspectival knowing – the knowing that comes through how we see and experience the world. As we sharpen our awareness so does our capacity for this kind of knowing.

- Participatory knowing – the most profound form of knowing, where the “I” is not apart from, but a manifestation of the indivisible relationship we have with reality.

It took me time to really digest and embody these ideas, so give yourself enough space to contemplate them.4

When it clicks, the implication is huge: True wisdom is a coming together of all the ways of knowing.

As the more integrated forms of knowing begin to come online, we can start to move from seeing ourselves as discrete entities trying to control and dominate reality around us, to realizing that we’re participants within reality, made of it, sustained by it, and inextricably woven into it’s unfolding.

Until our financial and societal systems reflect all forms of knowing, any effort to do something will keep pushing uphill.

For now, we’re still mostly trying to solve our meta-crisis through the left brain alone, through propositional knowing – analysis, metrics, policy, design. All of which are necessary, but not sufficient. We are missing the re-integration of, as Vervaeke might say: the intuitive, the relational, and the sacred.

Successfully doing something will depend as much on right-brain capacities such as empathy, imagination, and a felt sense of wholeness, as on our left-brain brilliance that has built and dominates our civilisation today.

So what do we do?

It’s easy to think this is all just armchair philosophizing. But something’s shifting. We can already see green shoots breaking through.

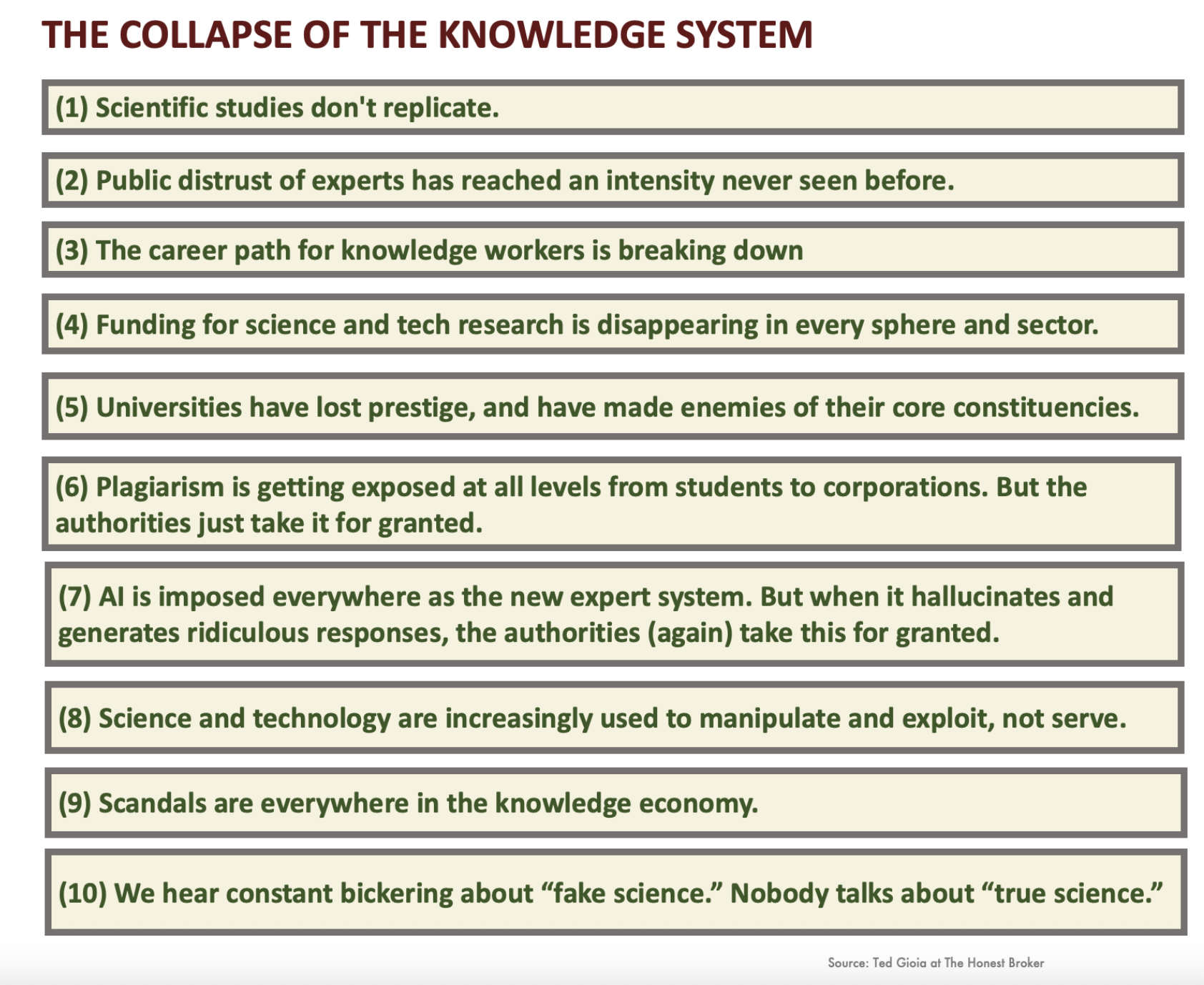

It’s coming in the growing awareness of how AI will soon collapse our knowledge economy which has been built on such a fragile foundation (hint: propositional knowing), and with it, talk of what might replace it: a wisdom economy. Im not sure I love the term as it risks sounding like an investment thesis, but the impulse behind it feels very right.

We can already see the early signs of a wisdom economy stirring in a fragile and largely uncoordinated way. The Inner Development Goals are an early attempt to give inner transformation a public framework, much like the Sustainable Development Goals did for our outer world. An explosion of therapeutic platforms have normalized psychological and emotional growth. And at the heart of a new era of community building, the World Wise Web is beginning to take shape, with Speira being among the first wisdom communities based in Asia.

That might say something about what the wisdom economy is today, in it’s infancy. But the more interesting question is: what might it become?

I recently launched Speira partly in response to what I see as an undeniable convergence of science, philosophy and ancient wisdom traditions finding common ground. Together, they’re giving rise to more integrated ways of understanding reality, new world views that draw from all the types of knowing. The movement points to a future wisdom economy where the materialist assumptions we’ve long taken for granted begin, finally, to be transcended and integrated.

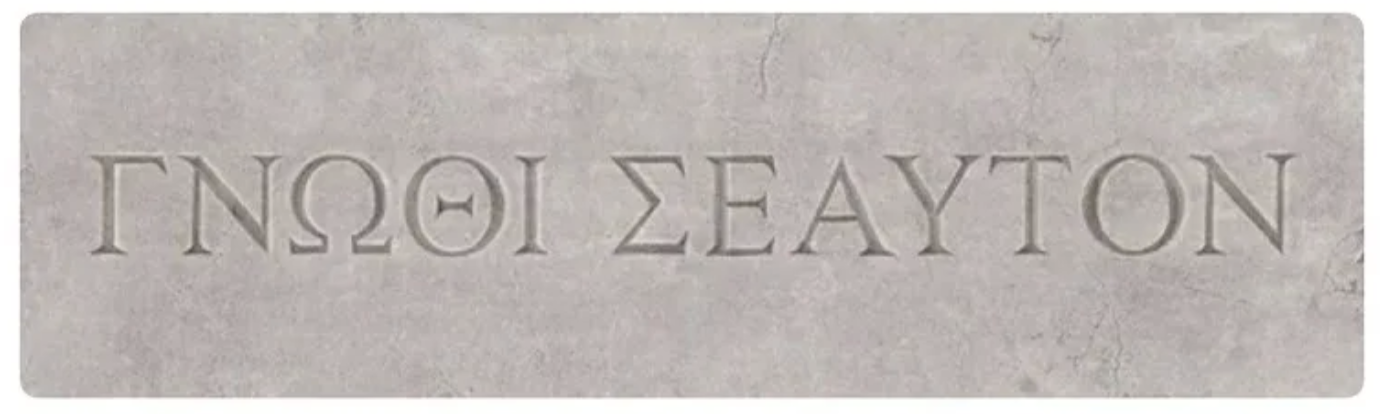

The wisdom economy might then best be thought of as an era that honors and integrates all the ways of knowing. And through that integration, society at large may embrace a new way of knowing the self.

But how do we get there? Transforming incentives is one thing, transforming identity is another - and an intensely personal journey at that. It requires a shift in perception, a re-remembering of who and what we are. It’s deeper, more cultural and spiritual in nature, and harder to “fund” in any conventional sense.

How could we even fund something like this? Could identity and perception shifts themselves become investable outcomes? Could we back ventures that help people move from seeing themselves as separate from our environment, to recognizing their inseparable connection with it? Can we create ways to measure belonging, ecological empathy, or relational coherence, and build the infrastructure to support them?

Can we hijack today’s incentive systems to drive and incentivize individual transcendence? What would that even look like? And does the very real potential for perverse outcomes make this too dangerous to even think about along these lines?

It’s both thrilling and daunting to imagine. These are deeply underserved lines of inquiry. And they might sound abstract today but they point to the kind of transformation that might be in store for our civilization.

In a wisdom economy, doing something might actually make a whole lot more sense.

Where do we begin?

Perhaps by not waiting for the perfect conditions. By doing what we can, if we feel called to act in the service of love. That will mean building within the systems that already exist. At best, these efforts will help spread a little more light into the world and hopefully reduce some suffering. At worst, they’ll serve as learning experiences. Perhaps even stepping stones and bridges, transitional structures that carry us toward a new paradigm, one that ultimately integrates the sacred.

I don’t pretend to have the answers. But the question of how to do something is one of the reasons I started Speira, a private community for conscious leaders and doers. We’re in the early stages of building it, and I’d love to hear from others who feel called to the same work. People actively engaged in the world, experimenting, creating, and trying to do things differently.

If by reading this you feel a spark of resonance in your chest or gut, please reach out. That’s the same spark I’m following, and I write with the hope that this will act as a sort of beacon to find the like-minded.

And I’ll leave you with a grounding thought. We tend to give ourselves way too much credit for what we think we can control. Even the assumption that the world needs to be fixed can be considered highly misguided when viewed from higher planes of awareness. The (s)elf is clever at disguising ego as purpose, blurring the line between autonomy and theonomy5.

This is a paradox not to be rushed, and it’s a challenge I continue to wrestle with. Yet there’s a simple rule that can help us re-align our intentions, again and again if need be, in the midst of it all: We should always remember that working on ourselves is, in fact, the ultimate form of doing something.

“If you are in truth attempting to make this a better world to live in, the most leverage you have is not on other people, it’s on yourself. You make yourself a statement of love. You make yourself a statement of truth. You make yourself a statement of consciousness. That is what changes the nature of the predicament that humans find themselves in now.”

– Ram Dass

Various carbon credit and other cap-and-trade programs have shown to drive behavior of the biggest polluters. ↩

Certain green loans and social impact bonds only pay out when certain targets are met. ↩

Certain green loans offer a discount if targets are hit, or a penalty if they are missed. ↩

If this sparks your curiosity, I can’t recommend highly enough John Vervaeke’s Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, a freely available lecture series exploring the cognitive science of meaning making and wisdom. ↩

Vervaeke uses the word theonomy to describe building a deep relationship with reality (“the sacred”) that actually strengthens our sense of agency instead of diminishing it. It’s different from the old religious idea of being ruled by divine law. If autonomy means being guided by yourself and heteronomy means being guided by others, then theonomy means being guided by something greater than the self ie. the divine. ↩

Member discussion